Victoria Law

New Politics (mayfirst.org) Vol:XII-4

Winter 2010: 48

IN 1974, WOMEN IMPRISONED at

New York's maximum-security prison at Bedford Hills staged what is known as the August Rebellion. Prisoner organizer Carol Crooks had filed a lawsuit challenging the prison's practice of placing women in segregation without a hearing or 24-hour notice of charges. In July, a court had ruled in her favor. In August, guards retaliated by brutally beating Crooks and placing her in segregation without a hearing. The women protested, fighting off guards, taking over several sections of the prison, and holding seven staff members hostage for two and a half hours.

Male state troopers and (male) guards from men's prisons were brought in to suppress the uprising, resulting in twenty-five women being injured. In the aftermath, twenty-four women were transferred to the Matteawan Complex for the Criminally Insane.

Three years earlier, male prisoners in

Attica, New York, captured headlines nationwide when they took over the prison for four days demanding better living and working conditions. The governor ordered the National Guard to retake the prison; 54 people (prisoners and guards) were killed. The rebellion catapulted prison issues into public awareness, becoming the symbol of prisoner organizing. In contrast, the August Rebellion is virtually forgotten today, leading to the widespread belief that women prisoners do not organize or resist.

Women prisoners have always resisted. When imprisoned in male penitentiaries and work camps, they refused to obey the rules. When states began housing them in separate facilities, they protested substandard conditions, sometimes violently. In 1835,

New York State opened its first prison for women. The environment was so terrible that the women rioted, attacking and tearing the clothes off the prison matron and physically chasing away other officials with wooden food tubs.[1]

A century later, women continued to protest horrifying prison conditions: In 1975, women imprisoned in

North Carolina held a sit-down demonstration demanding better medical care, improved counseling services, and the closing of the prison laundry. When prison guards attempted to end the protest by herding them into the gymnasium and beating them, the women fought back. Using volleyball net poles, chunks of concrete, and hoe handles, they drove the guards out of the prison. Their rebellion was quashed only after the state called in over one hundred guards from other prisons.[2]

Some instances of resistance remain little known outside the prison. Former political prisoner Rita "Bo" Brown recounts that women imprisoned in

Nevada took action against the prison's psychiatrist who had been pushing psychotropic medication, even to women who did not need it. One woman died as a result. Her death unleashed the women's anger. The next time the psychiatrist visited the prison, the women threw chairs, tables, and anything they could lift, driving him not only off-premises but also off the job. Not only was the psychiatrist replaced (with the prison's first woman psychiatrist who did not share her predecessor's enthusiasm for drugging patients), but so were the prison's doctor, warden, assistant warden, and other higher-ups in the prison administration.

The women's action did not make the news. Brown learned of it only after arriving at the prison itself two months later. Former political prisoner Laura Whitehorn also recounted tales of resistance that, were she not outside telling them, would have remained buried behind prison walls. When she first arrived at the Baltimore City Jail in 1985, she quickly learned that she would have to fight for her rights, even those she was entitled to under jail regulations, state law, and the constitution. "As a white middle-class woman, I really hate waiting on lines. I didn't want to. But I had to learn the difference between making that an issue, which no one else there thought was the big issue, and fighting for things that were really important to people. And taking leadership from the women who knew better than I did what was important to resist."

She recounted that, like many other jails and prisons, the food was almost inedible. "We had been hoping that at Thanksgiving, we would get a piece of turkey, something that was decent," she recounted. "Come Thanksgiving, they [the guards and administration] hand out these, I don't know, they were dinosaur legs! You could break a window with them. And, in this prison, when you come in and you had dentures, they would take your teeth away. So most of the women didn't have teeth.

I couldn't eat them with my big choppers and other women couldn't either. We were all furious. We marched out and we threw them all in the garbage and walked out. That was the first little bit of resistance around this issue.

"So me, with my 'We're going to make a revolution here,' I started talking to my friends. And I said, 'At Christmas, let's do a hunger strike,' or 'Let's throw the trays back at them' or something. And people were like, 'No, we don't want to do that.' And what they came up with, which was much better, was that we should not go to dinner that day. Just not go, and that we should organize the community people that came in, which were a nun, a teacher, a chaplain, and the decent guards to bring food and make a Christmas party. And so we got that. And the whole time I'm thinking 'Oh yeah, this is really revolutionary, a Christmas party.' Well, it was. Because it was saying 'Fuck you. You don't want to give us our rights but we're going to take them in this small way.' It was the most wonderful thing. It was really great."[3]

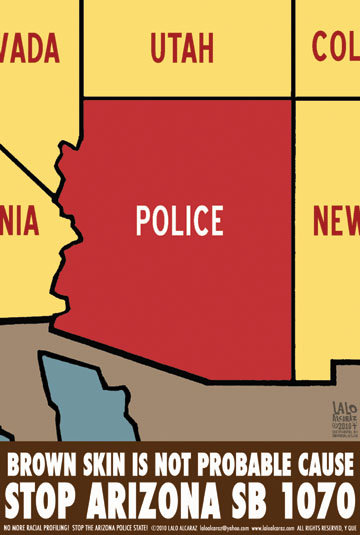

MORE RECENTLY, WOMEN INCARCERATED in

Arizona attempted to protest and draw public attention to the use of cages in

Arizona prisons. The only coverage was a short article in the

Arizona Republic.[4] The incident might have been forgotten had blogger Peggy Plews not taken on the issue, reprinting the article on her blog, reaching out to other prisoner rights advocates, organizing protest actions, and demanding accountability from Arizona prison and elected officials.[5] Arizona has more than 600 outdoor cages where prisoners are placed to confine or restrict their movement or to hold them while awaiting medical appointments, work, education, or treatment programs.[6] On May 20, 2009, Marcia Powell, a mentally ill 48-year-old incarcerated in Perryville, died after being left in an unshaded cage for nearly four hours in 107 degree heat. Two and a half weeks later, three women at the same prison simultaneously set fire to their mattresses in an attempt to draw outside attention to these conditions.[7]

Women have also resisted in less visibly dramatic ways. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 allows male guards to work in female prisons. Many states do not restrict guards' access to the women, often leading to sexual harassment, abuse, and assault. However, incarcerated women have resisted staff sexual abuse, both individually and collectively. One woman, incarcerated in

Ohio during the early 1990s, recounted that a male officer constantly harassed her cellmate. "He'd make nasty insinuations about her breasts and what he would like to do to them and how he would like to do it and what he'd do to her."[8] The guard threatened to place cocaine among their possessions if she or her friends reported his behavior. His threat worked; the women kept quiet about his harassment. One night, he assaulted his victim. Her cellmate and another prisoner heard her screams and found her with semen on her face. Despite their fears, the three filed a complaint with prison officials and later testified before a grand jury, leading to the officer's arrest and conviction. Their actions encouraged other women to resist male guards' abuse of power.

"It was a funny thing after that happened," the woman stated. "A lot of the nastiness and that vulgarness . . . was seeming to cease a little bit and to ease up a little bit, because they began to get nervous. And more women stood up, and two other officers were escorted off because the women found enough courage to stand up."[9]

Laura Whitehorn has a similar story from her incarceration at the federal prison in

Lexington, Kentucky.

There was this one guard. We called him "John Wayne." . . . He would pat-search us. They're not supposed to put their hands on our breasts or in between our legs, they're supposed to just go around the area. But he grabbed my breasts and squeezed them and so I rammed my elbow into whatever [body part] was nearest behind me. And he tried to lock me up. I was taken to the lieutenant's office.

One of the other dykes on the compound, who was a good friend, saw me. I said, "John Wayne just grabbed my breasts." She brought two others and they all stood outside the lieutenant's office, which is off-limits, and said, "We demand that this be taken seriously." And so they didn't lock me up . . .We then grieved it . . . And we lost. They said he had acted professionally. But the lieutenant . . . took two of us aside and said, "We want you to know that they're making John Wayne watch the training videos over and over again. And they didn't have him at the checkpoint where the most people go through."[10]

Although the women's actions did not remove "John Wayne" from the prison, it did warn him that his behavior would no longer go unchecked and removed him from working in areas where he could do the most harm.

Women have also organized collectively to limit male guards' access and abuse. In 1996, 500 women who had been sexually assaulted by guards while incarcerated in

Michigan filed

Neal v. MDOC. In July 2009, the suit was settled. Male guards were prohibited from entering areas in which women would be partially or fully undressed (i.e., sleeping, shower, and toilet areas). The settlement also provided for a $100 million settlement for the women who had been assaulted and payment of all legal fees.[11]

Another issue that women have organized around is education. Access to education is particularly important given that women in prison come from the groups least likely to finish high school or attend college: women in poverty, disproportionately African-American and Latina.[12]

In 1973, Michigan was one of several states that provided basic education programs in male but not female prisons.[13] In 1977, women imprisoned in Michigan's Huron Valley State Prison filed

Glover v. Johnson, a class-action suit claiming that prison officials violated incarcerated women's rights under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment by denying them access to the vocational and educational programs that were available to their male counterparts. When asked what prompted her to file the suit, lead plaintiff Mary Glover stated, "I wanted to go to college." Both she and her husband had been sentenced to prison. Her husband had the opportunity to enroll in both college and vocational programming. Glover, who was sent to the women's prison, did not.[14]

In 1979, the court ruled in their favor and ordered the state to establish a general education program for women that was the equivalent to the one offered to men.[15]

The court also ordered that the prison offer a course on legal skills to the women "because skilled women inmates are needed to provide access to the courts." In the court's opinion, although the prison law library met constitutional standards, women still lacked the access to the courts guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment's due process clause. Male prisoners had a tradition of jailhouse lawyering and thus had developed expertise in utilizing legal resources, but "the women do not have a history of self-help in the legal field; the evidence tends to show that until recently they have had little access to adequate resources."[16] Some of these women, including Mary Glover, took these courses and then went on to file other suits against MDOC (including

Neal v. MDOC).

Women have also organized to defend their access to educational programs. In 1972, radical feminists formed the Santa Cruz Women's Prison Project (SCWPP), the first program to ever offer university courses in a women's prison. In contrast to the prison's existing vocational programs, such as hairdressing, sewing, and office work, the SCWPP offered courses that challenged students to analyze the social issues affecting their lives, such as Women and the Law, Drug Use in U.S. Culture, and an Ethnic Studies course which focused on the historical and sociological perspective on women of color in the United States.[17]

The project also connected women inside with current events and foreign political struggles. After learning about the experiences of women in

Vietnam, women at CIW wrote letters of solidarity to women political prisoners in

Vietnam. The letters were not only delivered to the women imprisoned in

South Vietnam but also published as a pamphlet entitled

From Women in Prison Here to Women of Vietnam: We Are Sisters.

In 1972, when one of the SCWPP founders was temporarily banned from the prison and the program suspended, students organized a work strike and a sit-in before the warden's office.[18] When the project was barred again in 1973, the students circulated petitions, held work strikes, and met with the administration to protest the project's removal.

During one of the periods in which the project was banned, a woman who had been at the prison for years observed:

I witnessed something I would have believed [three years ago] was impossible. We had an [illegal] meeting where Black and White were united, under one common cause. There were women there who in the past would never have spoken to each other but here they were standing together, agreeing, touching shoulders. The tone of the meeting was not loud or wild. It was a confident approach to bringing back the workshops. It is something we all want. It was beautiful. We elected a six-woman committee to speak for the group. We are not afraid.[19]

The opportunity to critically examine issues affecting their lives and to challenge prevailing stereotypes built bridges between prisoners who had previously believed they had nothing in common. And, when this opportunity was threatened, these women already had the groundwork to set aside their differences and unite to pressure the prison to reinstate the program.

Even today, access to education has a tremendous impact on women behind bars, many of whom enter prison with low self-esteem, self-worth, and self confidence after years of physical and/or sexual abuse.[20] Marcia Bunney, incarcerated in California, recounted, "Difficult experiences at school during my childhood and adolescence had left me with memories of loathing conventional education and everything connected with it." The abuse that she had suffered in previous relationships had implanted the idea that she was not smart enough to attend college: "I was skeptical of the idea of returning to school, certain that college was beyond my ability, ready to give up before I had given myself a chance to start."[21]

However, without the continual discouragement of abusive lovers and with the encouragement of her fellow prisoners and her prison work supervisor, Bunney overcame her doubts and fears about education, earning an associates degree. That was not her only lesson: "Beyond the specific components of the curriculum, I learned many valuable lessons, the greatest of which was that I was

capable. After a lifetime of seeing myself as a failure and as inferior, this represented a complete reversal, one that admittedly required effort to accept and absorb."[22]

How is education linked to resistance? Women with more education are often sought by their peers. Broomhall observed that less literate women rely on others to write their requests to staff members. "They are simply incapable of clear expression," she noted.[23] Dawn, a woman incarcerated in

Texas, concurred: "Frequently, I will hear women ask someone to help them write a grievance." She also noted that when a woman writes a grievance about a condition affecting all or most of the women on her unit, others will copy her complaint. "They believe that there is some right or wrong way to fill these [grievance forms] out and that somehow they are not qualified to write on this 'official form,'" she noted. "It's very daunting to some of them."[24]

Education has also led women to challenge systemic abuses: both the writing skills and the self-confidence that Marcia Bunney gained during her college classes led her to learn to use the prison grievance system to dispute prison injustices. Prison officials transferred her to the Central California Women's Facility where she took advantage of her job as a library assistant and taught herself law. She joined the National Lawyers' Guild, becoming one of five prisoner representatives of the National Steering Committee of the Guild's Prison Law Project. She also initiated contact with an attorney known to be interested in litigating to change prison conditions: "Soon I was organizing the active acquisition of information to support claims of systematically inferior medical care, including the names and particulars of prisoners willing to come forward to be interviewed." In addition, Bunney began educating herself about civil litigation, again drawing on the skills she learned through her college classes: "My strong composition skills were an asset, and I grew adept at drafting clear, concise declarations as a means of documenting the serious medical problems of many women, including several who proceeded to file individual actions for damage."[25]

During the 1970s, outside activists and organizers recognized that the injustices occurring on the inside were exaggerated mirrors of those on the outside and often worked in solidarity with people in prison to challenge and change prison conditions. Today, although many on the left are alarmed about the trend of mass incarceration, few are making the personal connections with people inside resisting and organizing. Why aren't we connecting the struggles for social justice outside with those on the inside?

Incarcerated women and their advocates have suggestions on how activists and organizers on the outside can support their resistance behind bars:

- Make contact with women in prison. As a woman incarcerated in Florida put it, "Visits, phone calls, and letter writing are essential. Only with a firm foundation, a strong foundation, can we together be able to build a greater movement."

- Speak out or write about prison issues, especially when they intersect with issues that are considered "non-prison" issues.

- Raise awareness in other creative ways. Activists infuriated by Marcia Powell's death have been placing "Free Marcia Powell" signs in well-trafficked areas, spreading the word not only about her death but also systemic prison atrocities.

- Send literature and news from the outside.

- Participate in support organizations that include the participation and leadership of currently and/or formerly incarcerated women.

- Peer education groups need up-to-date information on health issues and treatments! They also need outside people who are willing to provide services not available (but much needed) within the prison.

- For those connected to universities or other educational institutions: look into setting up a women's studies course or other program within a women's prison that helps articulate and challenge the dominant ways of thinking and the power structure.

-----------------

1. Nicole Hahn Rafter,

Partial Justice: Women, Prisons and Social Control, 2nd ed. (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 1990), 17-18.

2.

The New York Times, "Women Inmates

Battle Guards in

North Carolina," June 17, 1975, 18.

3. Laura Whitehorn, "Women on the Margins: Incarceration and Resistance in the Current Era." Left Forum, Pace University, April 19, 2009.

4. Megan Boehnke,

"Three Perryville Inmates Set Mattresses on Fire in Goodyear," Arizona Republic, June 7, 2009.

5. In

an open letter to the director of the Arizona Department of Corrections, Charles Ryan, Plews asked: "What has the department done to the women who set their mattresses on fire in organized protest? It is my understanding that they are in administrative segregation now (commonly referred to as being put into the hole), and may only receive legal assistance if charged in criminal court; they are on their own defending themselves in internal disciplinary proceedings, even though the outcome could seriously affect the kind and length of time they end up doing in the long run."

6. Arizona Department of Corrections,

Chapter 700: Operational Security. Department Order 704: Inmate Regulations. 704.09: Temporary Holding Enclosures. (accessed July 7, 2009).

7. Peggy Plews,

"Smoke Signals in the Desert," Prison Abolitionist, June 7, 2009 (accessed July 7, 2009).

8. Patricia Gagne,

Battered Women's Justice: The Movement for Clemency and the Politics of Self-Defense (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1998), 185.

9. Gagne, 185.

10. Whitehorn. "Women on the Margins."

11. For more on the settlement, see

here.

12. Michelle Fine, Kathy Boudin, Iris Bowen, Judith Clark, Donna Hylton, Migdalia Martinez, "Missy," Rosemarie Roberts, Pamela Smart, Maria Torre and Debora Upegui,

Changing Minds: The Impact of College in a Maximum Security Prison, 2001.

13. R.R. Arditi, F. Goldberg, Hartle and Phelps, "The Sexual Segregation of American Prisons,"

Yale Law Journal 82 (1973): 1242.

14. Mary Glover, telephone interview with author, October 12, 2008.

15.

Glover v Johnson, 478 F. Supp. 1075 (E.D.Mich. 1979).

16.

Ibid.

17. Karlene Faith, "The

Santa Cruz Women's Prison Project, 1972-1976," in

Schooling in a "Total Institution": Critical Perspectives on Prison Education, ed. Howard S. Davidson. (Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey, 1995), 177-8, 180-181.

18. SCWPP founder Karlene Faith had ended a letter to a prisoner with the word "Venceremos" (literally "we will conquer"), a colloquialism that many activists used to indicate overcoming all obstacles to freedom. However, the guard who read her letter assumed that Faith was connected with a group called "Venceremos," which had claimed credit for an escape from a neighboring men's prison. Faith -- and the program -- was allowed to return to the prison only after a thorough investigation of her background (Faith, "Women's Prison Project,"182-3).

19. Faith, "Women's Prison Project,"185. Faith does not go into detail about what had caused that particular break in the program or what the women had resolved to do in that instance.

20. Caroline Wolf Harlow,

Prior Abuse Reported by Inmates and Probationers, special report for the U.S. Department of Justice, April 1999, 1.

21. Marcia Bunney, "One Life in Prison: Perception, Reflection and Empowerment," in

Harsh Punishment: International Experiences of Women's Imprisonment, ed. Sandy Cook and Susanne Davies (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999), 24.

22.

Ibid., 26.

23. Jerrye Broomhall, letter to author, January 30, 2008.

24. Dawn Reiser, letter to author, February 11, 2008.

25. Bunney, "One Life in Prison," 28-29.

Author Bio:

Victoria Law is a writer, photographer, and mother. She is a co-founder of Books Through Bars --

New York City, an organization that sends free radical literature and books to prisoners nationwide, and editor of the 'zine

Tenacious: Writings from Women in Prison. Her latest book,

Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles of Incarcerated Women, is the result of 8 years of listening to, writing, and supporting incarcerated women nationwide.

http://newpolitics.mayfirst.org/fromthearchives?nid=174