"Free Marcia Powell" Phoenix New Times.

December 17, 2009

Just came across these old blog posts about prison abolition and Marcia Powell from when I first started blogging. I thought they were worth resurrecting as this state continues to exterminate the lives of those we've collectively degraded and deemed less-than-worthy of medical care or the other basic necessities of life with Jan Brewer and Chuck Ryan at the helm. December 17, 2009

This should be enough to keep you busy for awhile...

There are a lot of misconceptions about exactly who's in prison in America, unfortunately, and what happens to them there. There are a few really bad guys, yes - but not everyone in prison is evil, nor is every bad guy behind bars (as evidenced by Russ Pearce's liberty). The law enforcement community even has to manipulate data to justify their funding by frightening people because the truth is on our side, not theirs.

Witness the Phoenix PD bullshitting the feds about our kidnapping rates (that's fraud, among other things), and the AZ Prosecuting Advisory Council trying to convince us that 95% of AZ state prisoners are REALLY dangerous criminals we can't have on the streets (by lumping stats on repeat drug and property offenders with the violent ones). They seem to have no problem letting abusive cops and guards slide, though, as long as their only victims were prisoners.

The high recidivism rate - one symptom of our corrections' system failures - has been twisted into a sign of law enforcement's success instead, as so many of our criminals are now presumably beyond reform - the best we can hope to do is catch and imprison them. Recidivism can be reduced by prison programs like substance abuse treatment, though - which could make a world of difference since 75% of AZ prisoners are assessed at intake as having substance abuse disorders. The ADC plans to add 8,500 more prison beds through 2017 and resists sentencing reform, but they only provided substance abuse treatment services to over 1,000 of the approximately 60,000 prisoners they confined in 2010 - and that includes people sent there for everything from DUI's to manufacturing meth!

I bet there were far more prisoners with dirty urines than in drug treatment at the ADC in 2010 - and more resources spent surveilling and punishing drug use throughout the system than preventing or treating it. In FY2010, three prisoners died of accidental drug overdoses; only one died of AIDS.

So WHAT are they doing with the rest of the addicted prisoners and all that treatment money, then? Clearly not rehabilitating them with it. And they sure aren't counseling all those addicts with Hep C in the hopes they clean up and undergo interferon treatment before returning to the community. After all, if they didn't test dirty for drugs in prison the ADC might have to consider providing them with real health care. Where would they ever get the money? So they're just letting people die. About a third of all AZ prisoner deaths are secondary to Hepatitis C. That's an epidemic that no one is talking about.

So WHAT are they doing with the rest of the addicted prisoners and all that treatment money, then? Clearly not rehabilitating them with it. And they sure aren't counseling all those addicts with Hep C in the hopes they clean up and undergo interferon treatment before returning to the community. After all, if they didn't test dirty for drugs in prison the ADC might have to consider providing them with real health care. Where would they ever get the money? So they're just letting people die. About a third of all AZ prisoner deaths are secondary to Hepatitis C. That's an epidemic that no one is talking about.Anyway, law enforcement's argument that we NEED more prison beds for the sake of public safety is contradicted by other facts. By the Arizona Department of Corrections' own report, out of approximately 40,000 prisoners in their custody, over 16,000 are housed in minimum security. Those are people who the department thinks pose so little threat to the rest of us that the only time they really need to be locked up is when they sleep...now that sounds like someone is just collecting steep rent ($20,000/year), not protecting and defending us from monsters. Much of the lower security confinement is done by private prisons, too.

Hmm.

Could there be a profit motive for someone to imprison petty offenders? Are prosecutors and judges getting brownie points for the number of years they put people away for, or for reducing crime rates in the community? How do we extract our collective justice from offenders and their families - is it in a way which perpetuates victimization or helps eradicate crime? Those are some of the questions I've been asking myself these past two years, examining the prison landscape up close.

Think real carefully now about whether or not you've ever done anything stupid or criminal enough to land a less-fortunate soul in prison - like one or two nights driving home with too many drinks on board. Few Americans have really been that squeaky clean. Know that the people behind those walls are a lot like most of the rest of us just trying to get by in this world: they just happened to have been successfully prosecuted (which isn't even to say that they're all guilty).

The main difference between defendants who get prison time and those who don't is whether or not they have the resources for a private attorney and power on their side, not whether or not they're truly despicable human beings - or that they even did what they were sent to prison for. Plenty of despicable human beings are wearing the badges and guns in this place, in fact, and too many decent souls - like Marcia Powell - are still ending up dying in chains at their hands...

- Peg

"Anarchy!"

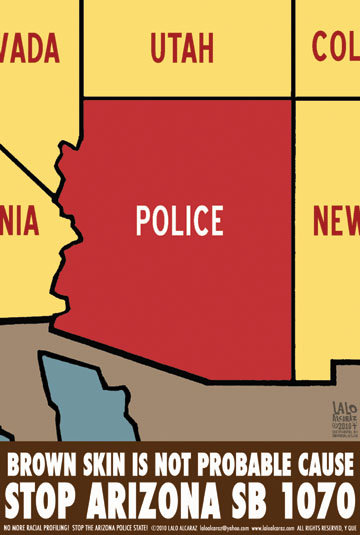

SB1070 sidewalk protest.

Phoenix, AZ (May 30, 2010)

-----------The Prison Abolitionist Archives------------------

I fell into this first through taking a class on capital punishment, taught by a former judge who had once helped author Arizona's post-Furman death penalty statutes. The weight of the evidence that capital punishment was so often applied in a racist, classist way (which not surprisingly catches the innocent) ultimately compelled him to change his position on the death penalty - something I found out only after the semester was over, as he didn't want to sway students by articulating his own position. He did a good job of just presenting evidence for both sides of the argument. Presenting both sides is not my intent here, however.

I understand the impulse for vengeance and retribution, and have heard the case that state executions still serve as a deterrent to potential murderers, but I don't know how any thoughtful American could examine the institution of capital punishment - I mean, really dig into Supreme Court cases (including dissents) and law journals - and not commit themselves to ending it.

At the same time I was getting deeper into my research (which focused primarily on the death penalty and the Bible Belt) I was taking a class on Social Movements and another class on Wealth Distribution and Inequality. From these I learned more about race and class in the broader criminal justice system, COINTELPro, political prisoners, and the PIC Abolition Movement. I not only read work by abolitionists such as Angela Davis, Joy James, and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, but I also read some of the works that seemed to originally radicalize some of them.

I considered whether or not I was really an abolitionist myself, or just a reformer. That question got into some deeply held beliefs and buried traumas that were necessary to confront before I could answer it. Bottom line, after I did all my research, is that the question I had to ask myself was whether I was just another white liberal who didn't condone (or actively work against) racism or classism, or if I was an anti-racist who fought against it in all its forms - beginning with racism's manifestation in me.

I came out an abolitionist, and signed up for a class on Prison Social Movements.

Most of us can agree, I think, that prisons are an extraordinarily expensive way to deal with manifestations of drug addiction, the consequences of poverty, and the fear of people who act on political or religious beliefs outside of the "mainstream" (white middle-class America). I suspect that those of us who abstain from "criminal activity" do so not because of what the state might do to us, but because we grew up believing it was morally wrong to steal, kill, cheat, and so on. Christian or not, most of us have some version of the Golden Rule in our conscience, and we strive to get through life without hurting others - an impossible task, given all the levels of hurt there are. But we try.

When one's ethical standards are compromised by trauma, mental illness, addiction, grief, desperate economic conditions, and fear we collectively respond with police to remove that person from our presence, instead of confronting them with a community norm on non-violence and proceed to exemplify it by helping them find other ways of meeting their needs, instead of subjecting them to the terrifying potentials of state violence.

For example, Marcia Powell, a 48 year old mother diagnosed with manic depression and treated with psychotropic drugs was sentenced to 27 months in prison for prostitution. 27 months. That seems extreme, even with prior offenses and a history of addiction. What actually happened to her was worse.

I never would have known about Marcia and her prison sentence except that she died this week after 4 hours in an outdoor, unshaded chain-link cage (like a dog pen) in midday desert heat. AZ corrections officials assert that the cage was solely being used as a temporary holding place for prisoners being transferred, implying that her involvement in a disturbance just necessitated segregation, perhaps for her own protection - and explicitly denying that she was caged under the Arizona sun as a form of discipline. According to a volunteer there, prisoners complain that punishment is precisely what the cages are used for.

Arizona's prison policies actually allow the use of such outdoor cages (though not for discipline), so long as prisoners are provided water (shade is not required) and stay out no longer than 2 hours. Ultimately she died within 20 feet - within eyesight - of the air conditioned prison guards responsible for monitoring her through their window.

One of the linked articles did note that though she was diagnosed bi-polar she was on medications "used to treat schizophrenia". There's often an overlap of symptoms and treatment regimens for those illnesses. In any event, such medications (psychotropics) almost always warn of an elevated risk of heat stroke. People being treated with these drugs shouldn't even be left in the sun for two hours. The fact that the Perryville prison complex incarcerates a number of folks with mental illness suggests medical malpractice on the part of a prescribing physician if he/she failed to advise against caging prisoners in the sun. This is basic pharmacy 101 - the link I provided to that info isn't even a medical site.

My first response to Marcia's death was outrage - I wanted those responsible from the guards on up to be prosecuted and punished for their "reckless disregard" for human life. I wanted them imprisoned for at least the 46 years that the leader of a local burglary ring got for stealing rich people's possessions (so far as I know he never assaulted them). Then I thought, if a new way of responding to violence doesn't come out of this, then what will it take for me to really change? What would justice for Marcia look like? And what would it mean to those responsible for her death and their families? And would it keep this from happening again?

Justice doesn't begin and end with prosecution and punishment. As convenient as it may be to see this incident as an aberration - like we thought Abu Ghraib was, until more evidence of torture emerged - it's not uncommon. And it's not all about the guards or prison administrators, I figured; it's about us, too.

What is it we do as a society that reduces those we select for removal, isolation, and confinement to subhuman status in the eyes of their keepers, and the minds of the rest of us. Every news article about this woman showed her dissheveled, terrified mug shot, described her troubled life, identified that her kids (if they acknowledged her motherhood at all) are "lost" in the foster care system - their abandonment is presented almost as another of her long list of crimes, which presumably justify her incarceration and being subject to abuse.

Marcia's picture exposes her fear, poverty, confusion, despair, shame, and a host of missing teeth suggesting a history of victimization. Her eyes are windows to a soul who looks as if she's been trapped behind bars, walls, and locked doors most of her life; never really free - never really safe - whether on the inside or out. She sure wasn't free and safe selling herself for survival.

Sadly, we never did right by people with severe mental illness even before de-institutionalization. 40 years ago Marcia would have probably been getting neglected or abused in a state psychiatric facility instead of a prison. Maybe she was. We can learn from that era of de-institutionalization - if we don't do abolition right, then deviant and desperate people just go from one oppressive institution to another. That's called transinstitutionalization. We don't want to go back to what used to be called psychiatric hospitals.

So I asked myself what I could do to help get justice for Marcia, and for all those other folks - people's moms and dads and kids and siblings locked away - who suffer and die in the custody of the state. Rally outside the prison with mental health activists? Lobby local legislators on jail alternatives for the mentally ill? Demand the prosecution and incarceration of those responsible, so that they might know the feelings of helplessness, humiliation and dehumanization prisoners endure? So that they might be raped, beaten, drugged, murdered or - for their own protection - placed in solitary confinement for years and go mad?

In other words, does going from one bad option to another really set people free? And does inflicting the same kind of harm on Marcia's killers that the PIC inflicted on her constitute justice? And does not invoking the full force of the PIC against DOC employees mean that they're "getting away" with her murder? Won't it embolden other corrections officers and cops if there's no criminal charges filed for their extreme indifference to human life?

Or is there something, perhaps, that the community can do to find out how this happened, challenge the policies of the department of corrections, and hold the individuals involved responsible for coming up with solutions - alternatives to putting people in cages - and for pouring their blood, sweat and tears into making prison alternatives work. "Sentencing" them to the years of hard labor it takes to restore run down housing so people like Marcia can live in it is hardly typical "community service", because it's not just about hammers and nails - it's about zoning ordinances and business opposition and people worried about more crime and neighborhood resources being inadequate to support high needs individuals - whether they're 'criminals' or ordinary senior citizens.

Going through something like siting a supported housing program (which can take years of 60-hour work weeks) can change a person in a fundamentally more positive way than rotting in prison for manslaughter. It forces one to make personal sacrifices, to take a stand for social justice, and to interact with other social justice activists. That kind of work sure changed me. And I think it would be a better way to make amends to the community than putting Marcia's killers in prison. It's too late for them to make amends to her.

If they succeed, we will all be the better off for it, and they will have perhaps evolved beyond the point where they might abuse power like that again. By thinking outside the narrow confines of what we've been told is justice, we could not only eliminate the use of these cages and promote systemic life-saving reforms, but we could use the need for 'offenders' to make restitution and some kind of reconciliation by creating more safe places for the vulnerable people in our communities. Prison sentences may satisfy a certain amount of vengeance and make us think we're safe, but they were never designed to allow for restitution and reconciliation (even when judges order restitution, prisoners make pennies a day - they can't support their own children, much less compensate for the loss of someone's property, freedom, limb, or life.)

Before I heard about Marcia I had learned that there are impoverished city blocks in sections of New York on which the state spends 1 million dollars a year on keeping residents from those neighborhoods in prison. New York is but one state that spends more on incarcerating people of color than it does on educating them. I wondered what that money could do if invested directly in the community, and how things would look if the community took direct responsibility for creating alternatives to "criminal justice", like Neighborhood Watch groups that serve not to catch or surveille potential criminals, but that instead serve as back-up support for neighbors who have no food, families facing foreclosure, youth exploited by the drug and alcohol industries, former prisoners shut out of work and educational opportunities, latch-key children, and all those most vulnerable to becoming victims of both interpersonal and state violence - the young, the old, the homeless, the disabled, the poor, women, and people of color.

Abolition isn't just about closing prisons and turning molesters and murders out on the streets - I too would have a problem with that. It's about local control over public funds that improve public safety, implement options for reconciliation, restitution, and treatment for those who harm others, assure that basic needs (housing, food, safety, health care, etc.) for community members are met, educate all ages on non-violent conflict resolution approaches, and transform our seige mentality about crime into an understanding of the complexities of human needs and behavior and an earnest sense of responsibility to eradicate the physical, social, and ideological structures that perpetuate both individual and state violence in American society.

At least that's what PIC abolition means to me right now. I still have a lot to learn, and am aware I need to be changing my thought patterns and language when referring to parties and institutions affected by or constituting the prison industrial complex. Reading abolitionist literature helps - much of it is quite scholarly and sound. Critical Resistance (see links) has been a fabulous resource for developing an abolitionist consciousness and concrete tools. Many of the "books to prisoners" projects are organized by anarchists and other abolitionists, rather than libraries, and my correspondence with some of these groups has been quite eye-opening. I'm considering trying to form such a collective here in Tempe (hence my email, 'radicalreads'), which would serve not only as a mechanism for filling book requests from prisoners, but also as a way of gathering with like-minded people over our shared humanity with prisoners to figure out how our community can stop depending so much on cops with guns locking scary people up in cages.

So, if this is your calling too, I'd love to hear from you - my email is at the top of the page. In the meantime, I'll try to keep current on posts about Marcia Powell's life and death and where we go from here.

Peace.

SB1070 sidewalk protest.

Phoenix, AZ (May 30, 2010)

-----------The Prison Abolitionist Archives------------------

Until Every Desert Cage is Gone

Saturday, May 23, 2009

I hope you found your way here because you share a desire to abolish the prison industrial complex, or are at least curious about what prison abolition is. It took me a number of months of research and feedback from a couple of professors who are abolitionists to figure out what the movement was about, and to clarify what abolition meant to me.

I fell into this first through taking a class on capital punishment, taught by a former judge who had once helped author Arizona's post-Furman death penalty statutes. The weight of the evidence that capital punishment was so often applied in a racist, classist way (which not surprisingly catches the innocent) ultimately compelled him to change his position on the death penalty - something I found out only after the semester was over, as he didn't want to sway students by articulating his own position. He did a good job of just presenting evidence for both sides of the argument. Presenting both sides is not my intent here, however.

I understand the impulse for vengeance and retribution, and have heard the case that state executions still serve as a deterrent to potential murderers, but I don't know how any thoughtful American could examine the institution of capital punishment - I mean, really dig into Supreme Court cases (including dissents) and law journals - and not commit themselves to ending it.

At the same time I was getting deeper into my research (which focused primarily on the death penalty and the Bible Belt) I was taking a class on Social Movements and another class on Wealth Distribution and Inequality. From these I learned more about race and class in the broader criminal justice system, COINTELPro, political prisoners, and the PIC Abolition Movement. I not only read work by abolitionists such as Angela Davis, Joy James, and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, but I also read some of the works that seemed to originally radicalize some of them.

I considered whether or not I was really an abolitionist myself, or just a reformer. That question got into some deeply held beliefs and buried traumas that were necessary to confront before I could answer it. Bottom line, after I did all my research, is that the question I had to ask myself was whether I was just another white liberal who didn't condone (or actively work against) racism or classism, or if I was an anti-racist who fought against it in all its forms - beginning with racism's manifestation in me.

I came out an abolitionist, and signed up for a class on Prison Social Movements.

Most of us can agree, I think, that prisons are an extraordinarily expensive way to deal with manifestations of drug addiction, the consequences of poverty, and the fear of people who act on political or religious beliefs outside of the "mainstream" (white middle-class America). I suspect that those of us who abstain from "criminal activity" do so not because of what the state might do to us, but because we grew up believing it was morally wrong to steal, kill, cheat, and so on. Christian or not, most of us have some version of the Golden Rule in our conscience, and we strive to get through life without hurting others - an impossible task, given all the levels of hurt there are. But we try.

When one's ethical standards are compromised by trauma, mental illness, addiction, grief, desperate economic conditions, and fear we collectively respond with police to remove that person from our presence, instead of confronting them with a community norm on non-violence and proceed to exemplify it by helping them find other ways of meeting their needs, instead of subjecting them to the terrifying potentials of state violence.

For example, Marcia Powell, a 48 year old mother diagnosed with manic depression and treated with psychotropic drugs was sentenced to 27 months in prison for prostitution. 27 months. That seems extreme, even with prior offenses and a history of addiction. What actually happened to her was worse.

I never would have known about Marcia and her prison sentence except that she died this week after 4 hours in an outdoor, unshaded chain-link cage (like a dog pen) in midday desert heat. AZ corrections officials assert that the cage was solely being used as a temporary holding place for prisoners being transferred, implying that her involvement in a disturbance just necessitated segregation, perhaps for her own protection - and explicitly denying that she was caged under the Arizona sun as a form of discipline. According to a volunteer there, prisoners complain that punishment is precisely what the cages are used for.

Arizona's prison policies actually allow the use of such outdoor cages (though not for discipline), so long as prisoners are provided water (shade is not required) and stay out no longer than 2 hours. Ultimately she died within 20 feet - within eyesight - of the air conditioned prison guards responsible for monitoring her through their window.

One of the linked articles did note that though she was diagnosed bi-polar she was on medications "used to treat schizophrenia". There's often an overlap of symptoms and treatment regimens for those illnesses. In any event, such medications (psychotropics) almost always warn of an elevated risk of heat stroke. People being treated with these drugs shouldn't even be left in the sun for two hours. The fact that the Perryville prison complex incarcerates a number of folks with mental illness suggests medical malpractice on the part of a prescribing physician if he/she failed to advise against caging prisoners in the sun. This is basic pharmacy 101 - the link I provided to that info isn't even a medical site.

My first response to Marcia's death was outrage - I wanted those responsible from the guards on up to be prosecuted and punished for their "reckless disregard" for human life. I wanted them imprisoned for at least the 46 years that the leader of a local burglary ring got for stealing rich people's possessions (so far as I know he never assaulted them). Then I thought, if a new way of responding to violence doesn't come out of this, then what will it take for me to really change? What would justice for Marcia look like? And what would it mean to those responsible for her death and their families? And would it keep this from happening again?

Justice doesn't begin and end with prosecution and punishment. As convenient as it may be to see this incident as an aberration - like we thought Abu Ghraib was, until more evidence of torture emerged - it's not uncommon. And it's not all about the guards or prison administrators, I figured; it's about us, too.

What is it we do as a society that reduces those we select for removal, isolation, and confinement to subhuman status in the eyes of their keepers, and the minds of the rest of us. Every news article about this woman showed her dissheveled, terrified mug shot, described her troubled life, identified that her kids (if they acknowledged her motherhood at all) are "lost" in the foster care system - their abandonment is presented almost as another of her long list of crimes, which presumably justify her incarceration and being subject to abuse.

Marcia's picture exposes her fear, poverty, confusion, despair, shame, and a host of missing teeth suggesting a history of victimization. Her eyes are windows to a soul who looks as if she's been trapped behind bars, walls, and locked doors most of her life; never really free - never really safe - whether on the inside or out. She sure wasn't free and safe selling herself for survival.

Sadly, we never did right by people with severe mental illness even before de-institutionalization. 40 years ago Marcia would have probably been getting neglected or abused in a state psychiatric facility instead of a prison. Maybe she was. We can learn from that era of de-institutionalization - if we don't do abolition right, then deviant and desperate people just go from one oppressive institution to another. That's called transinstitutionalization. We don't want to go back to what used to be called psychiatric hospitals.

So I asked myself what I could do to help get justice for Marcia, and for all those other folks - people's moms and dads and kids and siblings locked away - who suffer and die in the custody of the state. Rally outside the prison with mental health activists? Lobby local legislators on jail alternatives for the mentally ill? Demand the prosecution and incarceration of those responsible, so that they might know the feelings of helplessness, humiliation and dehumanization prisoners endure? So that they might be raped, beaten, drugged, murdered or - for their own protection - placed in solitary confinement for years and go mad?

In other words, does going from one bad option to another really set people free? And does inflicting the same kind of harm on Marcia's killers that the PIC inflicted on her constitute justice? And does not invoking the full force of the PIC against DOC employees mean that they're "getting away" with her murder? Won't it embolden other corrections officers and cops if there's no criminal charges filed for their extreme indifference to human life?

Or is there something, perhaps, that the community can do to find out how this happened, challenge the policies of the department of corrections, and hold the individuals involved responsible for coming up with solutions - alternatives to putting people in cages - and for pouring their blood, sweat and tears into making prison alternatives work. "Sentencing" them to the years of hard labor it takes to restore run down housing so people like Marcia can live in it is hardly typical "community service", because it's not just about hammers and nails - it's about zoning ordinances and business opposition and people worried about more crime and neighborhood resources being inadequate to support high needs individuals - whether they're 'criminals' or ordinary senior citizens.

Going through something like siting a supported housing program (which can take years of 60-hour work weeks) can change a person in a fundamentally more positive way than rotting in prison for manslaughter. It forces one to make personal sacrifices, to take a stand for social justice, and to interact with other social justice activists. That kind of work sure changed me. And I think it would be a better way to make amends to the community than putting Marcia's killers in prison. It's too late for them to make amends to her.

If they succeed, we will all be the better off for it, and they will have perhaps evolved beyond the point where they might abuse power like that again. By thinking outside the narrow confines of what we've been told is justice, we could not only eliminate the use of these cages and promote systemic life-saving reforms, but we could use the need for 'offenders' to make restitution and some kind of reconciliation by creating more safe places for the vulnerable people in our communities. Prison sentences may satisfy a certain amount of vengeance and make us think we're safe, but they were never designed to allow for restitution and reconciliation (even when judges order restitution, prisoners make pennies a day - they can't support their own children, much less compensate for the loss of someone's property, freedom, limb, or life.)

Before I heard about Marcia I had learned that there are impoverished city blocks in sections of New York on which the state spends 1 million dollars a year on keeping residents from those neighborhoods in prison. New York is but one state that spends more on incarcerating people of color than it does on educating them. I wondered what that money could do if invested directly in the community, and how things would look if the community took direct responsibility for creating alternatives to "criminal justice", like Neighborhood Watch groups that serve not to catch or surveille potential criminals, but that instead serve as back-up support for neighbors who have no food, families facing foreclosure, youth exploited by the drug and alcohol industries, former prisoners shut out of work and educational opportunities, latch-key children, and all those most vulnerable to becoming victims of both interpersonal and state violence - the young, the old, the homeless, the disabled, the poor, women, and people of color.

Abolition isn't just about closing prisons and turning molesters and murders out on the streets - I too would have a problem with that. It's about local control over public funds that improve public safety, implement options for reconciliation, restitution, and treatment for those who harm others, assure that basic needs (housing, food, safety, health care, etc.) for community members are met, educate all ages on non-violent conflict resolution approaches, and transform our seige mentality about crime into an understanding of the complexities of human needs and behavior and an earnest sense of responsibility to eradicate the physical, social, and ideological structures that perpetuate both individual and state violence in American society.

At least that's what PIC abolition means to me right now. I still have a lot to learn, and am aware I need to be changing my thought patterns and language when referring to parties and institutions affected by or constituting the prison industrial complex. Reading abolitionist literature helps - much of it is quite scholarly and sound. Critical Resistance (see links) has been a fabulous resource for developing an abolitionist consciousness and concrete tools. Many of the "books to prisoners" projects are organized by anarchists and other abolitionists, rather than libraries, and my correspondence with some of these groups has been quite eye-opening. I'm considering trying to form such a collective here in Tempe (hence my email, 'radicalreads'), which would serve not only as a mechanism for filling book requests from prisoners, but also as a way of gathering with like-minded people over our shared humanity with prisoners to figure out how our community can stop depending so much on cops with guns locking scary people up in cages.

So, if this is your calling too, I'd love to hear from you - my email is at the top of the page. In the meantime, I'll try to keep current on posts about Marcia Powell's life and death and where we go from here.

Peace.

----------------------------

The Light in us All

Monday, May 25, 2009

This is the photo that the Department of Corrections had posted on their website in Marcia's record at the time of her death, which was so widely circulated in the press. She appears frightened, traumatized, disheveled, and likely very depressed. It may evoke pity - and apparently contempt among some - but it doesn't invite empathy, or leave open the possibility for most that Marcia could have just as easily been their mother, daughter, sister, or friend.

I've been reading chats about her today that appear to be written by people too ashamed of their comments to use their real names. Yet many seem to be enough at home with eachother in their chat rooms that they don't hesitate to ridicule a dead woman for falling victim to circumstances few of us could have endured for 48 years. I haven't blogged all day just because I've been so sick from what I've read.

This photo below, now on the ADC website (but not in the press), appears to be from several years earlier, before decades of addiction, poverty, and mental illness began to take their toll. Perhaps had the press used this photo, fewer people would be so quick to speak about her as if she were trash, or of less significance than a dog. She was once a vibrant woman whose smile belied the trauma she'd already endured. She was a living soul, and in both images, if we look beyond what we've been told, it's not that hard to see the light of God in her, as the Quakers are fond of saying.

The Light of God.

I don't consider myself religious, but I do think that life is sacred and the Mystery that causes our hearts to beat, our faces to smile, our arms to hug, our stomachs to turn, our eyes to tear, our minds to open or close, our souls to grieve, and the deepest part of our being to long to be better than we are is not a Power to take lightly. Whether or not her life was worth saving shouldn't even be up for debate. How we respond to this tragedy ultimately says nothing about Marcia; it says everything about what kind of people - what kind of community- we are.

Fortunately not everyone is so callous or cruel - I know there are folks out there who would do something if they could to set justice right for Marica and all those who struggle each day just to survive. There's actually a lot we can do; it's worth repeating.

Contact elected officials and demand an independent inquiry.

Write letters to the editor expressing your outrage and sadness over her death - don't bury it in a chat or a blog.

Organize or attend a vigil or memorial with members of your community. Vigils for prisoners who died at the hands of the state give permission to the frightened families of other prisoners to open up to their neighbors, speak about their experience, and stop living in shame.

Make a donation in Marcia's memory to a prisoner support or a prison abolition or reform program.

Let the Department of Corrections know that some of us expect prisoners to be treated better than that - we want them to come out healthier and saner than when they went in, not more disturbed or despairing. We need them at their best if they're going to come home to our neighborhoods, workplaces, and schools. Otherwise, what's the point of putting them away in the first place?

And don't bother arguing with those who are just entertained by your concern. They aren't likely to abandon their bigotry, especially if it's the only thing that makes them feel superior to others. Talk instead to open minds and compassionate souls who just need a little encouragement to take constructive action - to be the change.

Finally, we must all insist that they tear down those cages in the sun.

-------------------------

Just Listening

Friday, May 29, 2009

If I've seemed unusually quiet the past few days, it's because I've been trying to listen, processing what different people have had to say in the past week about Marcia's death and where we might go from here.I'm still trying to map the terrain out here; there's so much I don't know, from who runs the community center around the corner to just what an abolitionist would do to keep society safe from cannibalistic pedophiles and corporate sociopaths. I'm still not sure how to answer that, though the INCITE! Anthology has a really good piece on reconciling anti-violence work with abolition work, written along with folks at Critical Resistance.

A number of people have been touched to some degree by this tragedy. Even in chat rooms where people are a little more free to be cruel, the majority have expressed some sense of injustice at Marcia's death. What concerns me about the tone of it, though, is that most of those also express the expectation that even this incident won't result in substantial reform.

I've heard the same thing from politicians, journalists and seasoned advocates here as well. The struggle has gone on a long time; I'm sure it gets discouraging. When I look at the movement, though, I can't help but believe that another world is possible. This past week, in the course of developing this blog, I've dropped in on abolition projects and radical scholars, discovered new sites for prisoner artwork and writings, and taken comfort in the compassionate response of the peace and justice community to the life and death of Marcia Powell. Local people working on prison reform and abolition have come more clearly into view across disciplines and sectors of the community. I have no worries that Marcia's death will be swept under the rug with people like them around. They won't let it happen.

More importantly, perhaps, people ordinarily not concerned with prison conditions have taken notice and taken stands against cages and excessive sentencing. Politicians are trying to articulate some of the systemic flaws that led to Marcia's criminalization instead of to community treatment. Mainstream media outlets are publicizing the details of Marcia's memorial service, suggesting that her death is news that a broader segment of the community might be interested in. Today the AZ Department of Corrections formally suspended use of the uncovered outdoor cells. I'm not sure how encouraging the news is that they'll be "retrofitting" them with roofs and water instead - I have a visceral reaction to the use of cages at all. But it's a start. I don't know what took them so long.

None of this is to say that I think we're on the brink of radical systemic change. And I'm well aware that some progressive agendas still tend to accommodate oppressive institutions, putting off the day when real transformation can finally be brought about. I hate the idea of making inhumane systems function "better" when they simply need to be eliminated. But we also can't just leave people to die while trying to overthrow the carceral regime.

No comments:

Post a Comment